IB World Schools

To become an IB World school, educational institutions must meet rigorous standards of excellence set by the International Baccalaureate Organisation. (IBO) To date, approximately 5200 schools have been accredited with IB certification in over 140 countries around the globe. The Head Office is located at The Hague, Geneva, Switzerland and regional offices set up to support schools in Washington, Cardiff and Singapore. The IB Diploma Programme (DP) is highly acclaimed by universities around the world for providing students with a competitive edge to pursue their higher educational studies. To this end, a growing trend for schools intending to adopt IB education as their approach is evident.

Specifically in Japan, it seemed only recognised international schools in urban areas were offering the IB programme however, two years after the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 2011, plans were brought about for reform, the Ministry of Education established a consortium with the aim to revitalise educational practices.

In 2016, Sunnyside International School was awarded with Japan’s first, IB Primary Years Programme (PYP) accreditation as an nationally-recognised school. (so called Article 1 schools in Japan) In conjunction with this, Hisayuki Watanabe was also elected to represent Asia Pacific as one of twelve Head of Schools within the Global IB Heads Council due to his active contribution in promoting the IB across Japan.

IB Mission Statement

The International Baccalaureate® aims to develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect.

To this end the organization works with schools, governments and international organizations to develop challenging programmes of international education and rigorous assessment.

These programmes encourage students across the world to become active, compassionate and lifelong learners who understand that other people, with their differences, can also be right.

Although globalisation offers new opportunities for us to strive towards a common vision of world peace, current conflicts of interest amongst nations are still leading to obstacles being faced in this pursuit. Through the IB, we can prevent repeating mistakes of war and suffering from times past and rebuild education to provide the next generations of humankind with the inspiration and skillset to contribute to a better world.

Why IB?

In this day and age, global interdependence is a fundamental reality that cannot be ignored. It is an age of globalisation. Problem solving requires us to see beyond our personal and national boundaries as we face issues which affect the whole world; an example includes the impact of global warming on our planet earth. To address our current global issues, the United Nations (UN) have created their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) project.

As we seek solutions to reaching these goals, it is imperative our young and future generations continue to promote the survival of mankind and our world in collaboration with each other. However, can we be sure that our current and long-standing Japanese educational system provides for this?

Within the core of IB philosophy stands the traits of the Learner Profile which include descriptions of learners with thoughtful and balanced character. (See below for full description.) Although within the IBPYP, which begins at the age of 3 years, learning and teaching encourages the child to think for themselves, current educational practice in Japan often focuses on an approach which emphasises the teacher’s delivery of knowledge and understanding. Yet, it is apparent that we live in a world which requires us to embrace change at an alarming speed. An ability to adapt to these circumstances requires us to expose children to exploring and enhancing a range of skills through inquiry. For instance, we need to nurture each child’s critical thinking and creativity in solving problems and to achieve this, it is vital we enable children to actively participate in the learning process beyond absorbing given information.

As education around the world transforms to meet the needs of our current times, Japan is required to further pursue a paradigm shift and prepare to embrace change. It can be noted however that Initial steps are being taken and can be seen where growing exposure to the concept of ‘Active Learning’ is spreading. This movement aligns well with a key feature of IB philosophy promoting ‘inquiry-based’ learning which recognises the importance of supporting children in their personal journeys of discovery. Yet, is this really enough?

A need for change

It can be said that ‘Juku’ or ‘cram’ school is an accepted way of daily life and learning for children and young adults in Japan and surprisingly continues to encroach on an even younger range of children. Most students attend several classes until late evening each week and we can only wonder what impact this must be having on their mental and emotional well-being. Yet, why does it continue to exist as it does?

Unfortunately, like in many cultures, Japanese social norms define the measure of success for each learner through their performance in national or university entrance examinations. In other words, the ultimate goal for learning is to gain acceptance to a renowned, prestigious university. This implies that the ability for retained knowledge is still valued above the capability to think critically and apply acquired skills.

More recently, Japanese universities had dabbled with the idea of assessing rational thinking skills as part of the admissions process however, opinions from various bodies contest the proposal, suggesting it as unfair and impossible. School educators were strongly opposed to the implementation which inevitably resulted in these discussions being stopped in its tracks. If appropriate professional development measures were provided for teachers, would it not be possible, as the IB has long been doing so, for assessments to also be undertaken in the form of meaningful, research papers and dissertations?

This applies for English language acquisition in Japan as well. The significance of obtaining English as an additional language has long been accepted as a desired and required skill for global communication. Again, discussions regarding assessment of English language acquisition beyond test-based performance were quashed for lack of courage to value its purpose over traditional methods. This fixed mindset for assessment prevents learning to have a meaningful and relevant purpose and leaves Japan’s educational system lacking in preparing students for the real world and to think for themselves.

This is the current state of Japanese education; it is indeed in need for drastic reform.

Teaching Quality

ITo become an IB educator, high standards and practices are required to be met. At a minimum, national teaching certification is a requirement and continuous, intensive professional development is an expectation to be met by all teachers involved in learning and teaching at the school. In recognition of this, IB schools are required to provide opportunities for development in teachers to enhance their teaching and be effective educators. This means schools are required to assign sufficient budgets for workshops and training opportunities to support the life-long learning of their school community.

In comparison, the traditional practice of relying predominantly on the textbook approach for teaching and learning is still widely exercised in Japanese schools. It would be understandably challenging for teachers in learning environments like this to promote student agency and individualised learning.

To this end, IB education might be set at a higher fee in comparison to other programmes and schools however it remains undisputed that it does offer a broad and rigorous curriculum led by passionate and highly capable staff who can inspire students by example.

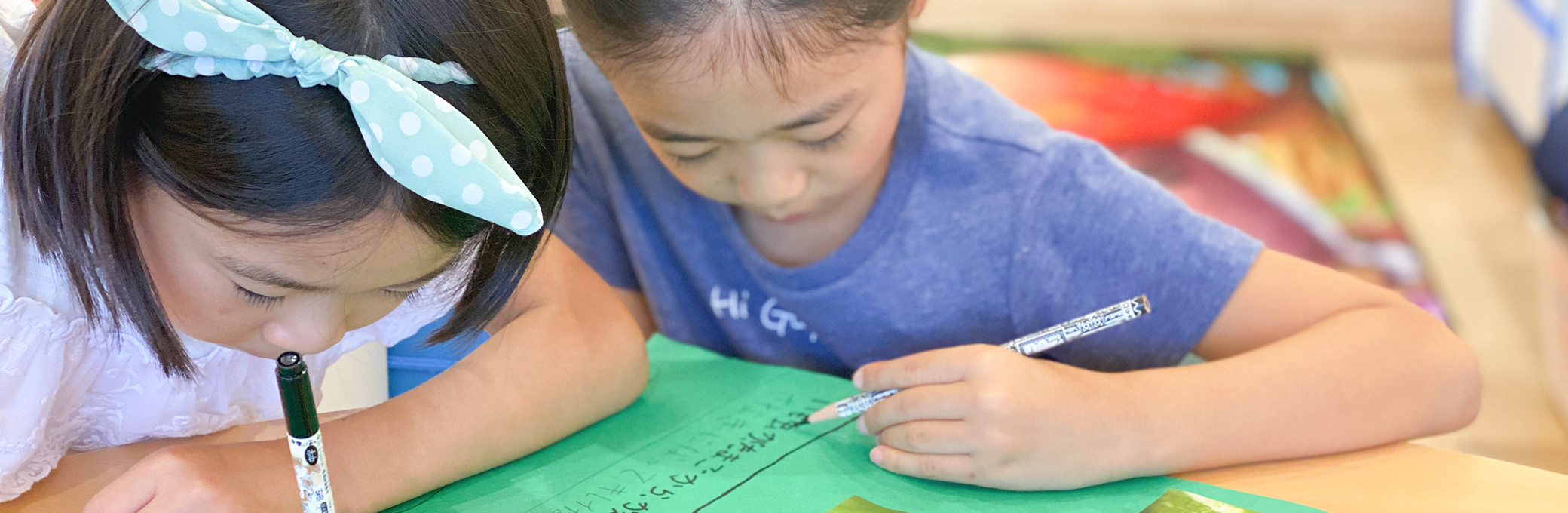

Thinking promotes Action

Research has been conducted to identify what makes IB graduates desirable students from a universities’ perspective. These studies conclude that IB graduates acquire characteristics of applying active and creative thinking skills. The PYP provides the first step towards this by promoting students to use their understanding as a base to take action. It supports students to recognise their learning as meaningful and consider how they can participate in solving a problem they encounter. Actions can range from a change of mindset or advocating for a cause they are passionate about.

Repeating this action cycle through experience and practice, children can begin to envisage how they fit into society and what they can do to contribute to make a difference as a valued individual in their community. By seeking their purpose at a young age, children will grow as young adults who choose to attend higher education in pursuit of realising their dreams.

International mindedness

Although there are many views in defining ‘international mindedness,’ we could generalise this concept as being open-minded to diverse perspectives and values. Although this idea is gradually seeping into the Japanese mindset, compared to other nations, there still needs to be greater efforts made in exploring what this truly means.

‘Ijime’ has been long identified as a unique trait of Japanese culture where ‘being different’ is frowned upon and needless to say, often a reason given for targets of bullying in various social spheres in Japan.

The IB philosophy provides the learning community to explore the roots of what makes us human and reflect on our behaviour and attitude towards others to reach the goal of international mindedness. It is our vision to nurture learners who understand, believe and feel they can act on what they think is ‘not right’ in terms of this.

IB Learner Profile

The IB learner profile represents 10 attributes valued by IB World Schools.

We believe these attributes, and others like them, can help individuals and groups become responsible members of local, national and global communities.

The profile aims to develop learners who are:

Inquirers

We nurture our curiosity, developing skills for inquiry and research. We know how to learn independently and with others. We learn with enthusiasm and sustain our love of learning throughout life.

Knowledgeable

We develop and use conceptual understanding, exploring knowledge across a range of disciplines. We engage with issues and ideas that have local and global significance.

Thinkers

We use critical and creative thinking skills to analyse and take responsible action on complex problems. We exercise initiative in making reasoned, ethical decisions.

Communicators

We express ourselves condently and creatively in more than one language and in many ways. We collaborate effectively, listening carefully to the perspectives of other individuals and groups.

Principled

We act with integrity and honesty, with a strong sense of fairness and justice, and with respect for the dignity and rights of people everywhere. We take responsibility for our actions and their consequences.

Open-minded

We critically appreciate our own cultures and personal histories, as well as the values and traditions of others. We seek and evaluate a range of points of view, and we are willing to grow from the experience.

Caring

We show empathy, compassion and respect. We have a commitment to service, and we act to make a positive difference in the lives of others and in the world around us.

Courageous

We approach uncertainty with forethought and determination; we work independently and cooperatively to explore new ideas and innovative strategies. We are resourceful and resilient in the face of challenges and change.

Balanced

We understand the importance of balancing different aspects of our lives—intellectual, physical, and emotional—to achieve well-being for ourselves and others. We recognize our interdependence with other people and with the world in which we live.

Reflective

We thoughtfully consider the world and our own ideas and experience. We work to understand our strengths and weaknesses in order to support our learning and personal development.

The International Baccalaureate® (IB) learner profile describes a broad range of human capacities and responsibilities that go beyond academic success. Some practicing advocates of the programme would even go as far as to say that to achieve these traits encompasses the vision of what the IB promotes. Each and every IB school will adopt the IB Learner Profile as a common language and places the utmost value on these traits within its learning community.

We are all Lifelong Learners

The IB values ‘lifelong’ learning as an essential feature for every individual. In Japan, the phrase, ‘shogai-gakushu’ is becoming more widely used as we enter an era experiencing change at an exponential rate. Obtained knowledge is no longer enough of a commodity to acquire for the workplace; continuous learning of new concepts and skills is now an expectation and requirement. This also does not apply to young learners alone. All individuals need to build awareness of their role to pursue the desired qualities shared by the IB and actively participate as learners amongst a supportive community.。

Connecting with IB Community

Over 140 countries offer IB schools striving to develop individuals who wish to contribute towards world peace. Each school shares its own unique values and beliefs but are connected and aligned through their shared vision of the IB philosophy. Technological advances such as the internet has enabled IB schools worldwide to connect and share information and has widened the opportunities for connecting beyond the school community and provided for deepened understanding of diverse perspectives. In this digital age, striving for international mindedness has become an achievable reality and opened paths to strengthening links between members of the IB World community.

Links

Official International Baccalaureate Website

https://www.ibo.org/

Japan Ministry of Education IB Consortium

https://ibconsortium.mext.go.jp/

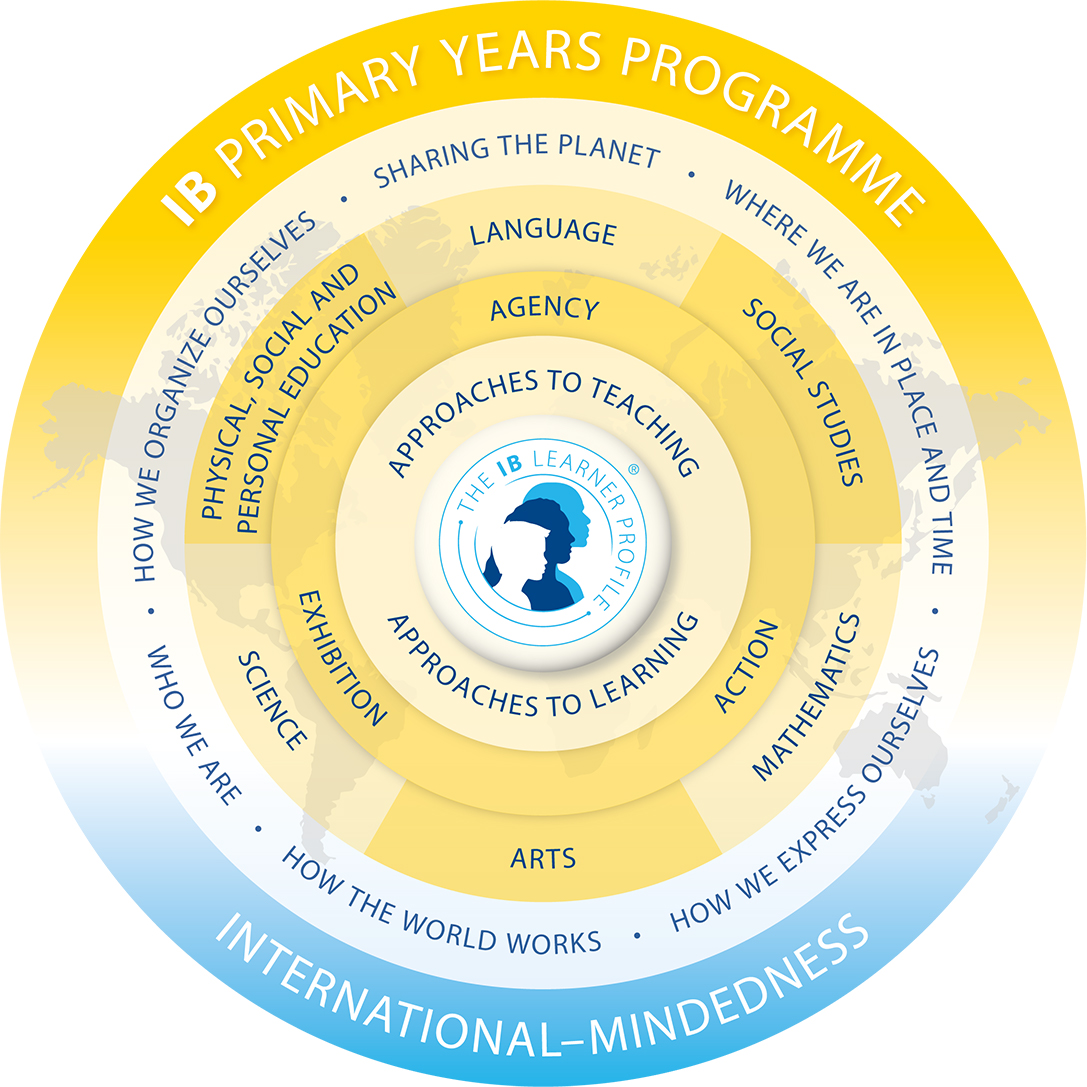

Key features of the Primary Years Programme (PYP)

The PYP is designed for learners between the ages of 3 to 12 years old and approximately 1700 PYP schools have been established around the world

Implementation of the programme encompasses schools of any language of instruction and a trend for Japanese educational institutions considering the adoption of the PYP is apparent.

Concept-based learning

The PYP promotes transdisciplinary learning; namely the approach to learning beyond subject-specific or discipline-based learning and teaching. Six themes are selected to represent the knowledge learners will explore within the school’s chosen unit of inquiries.

- Who we are

- How we express ourselves

- Where we are in place and time

- How we organize ourselves

- How the world works

- Sharing the planet

Transdisciplinary Themes:

Approaches to Learning (ATL) Skills

Tools of learning are nurtured as a key element within the PYP and classified as five main skills:

- Self-management Skills

- Social Skills

- Research Sills

- Thinking Skills

- Communication Skills

language

language